Underpromising and overdelivering in the age of the software-defined vehicle

In an era in which mainstream brands like Audi, Volkswagen and Tesla as well as start-ups such as Fisker, are asking customers to put their faith in an entirely new technology, maybe OEMs are better off underpromising and overdelivering, writes Drew Smith

The Rabbit R1 and the Humane AI Pin were, until recently, heralded as the dawn of a new age in personal computing. Infused with “artificial intelligence” and wrapped in hardware shaped by superstar designers (Teenage Engineering for the R1, former members of Apple’s Industrial Design Group for the AI Pin), here were two products that, according to their makers, were going to change the world or, at the very least, the way we interacted with computers for the better.

We would speak to them and have them respond as if they were our personal assistants. Their cameras would capture, analyse and categorise the world around us, giving us unparalleled insight. Their agents would accomplish feats of lifestyle management with nothing more than a spoken command. By virtue of their smarts, so the promises went, we would be able to leave the distractions of our phones behind to be more present in the world.

And yet to read and watch the reviews is to learn that this new dawn is unlikely to rise, at least not for Rabbit and Humane. So laughably incomplete and unfinished are these products that they’re unable to reliably fulfil even their most basic functions, to say nothing of their game-changing mission.

Marques Brownlee, a YouTube technology reviewer with 18.8m subscribers, called the AI pin the worst product he’s ever reviewed, and the R1 “barely reviewable”.

Once upon a time, it was unthinkable that a car maker would launch a product in such an unfinished state. For companies built around cultures of safety and all too aware of the cost of recalls, cars have *had* to be right first time out.

Extensive periods of pre-production validation have made this the norm rather than the exception. And yet over the past couple of years we’ve started to see car companies push out unfinished or ill-conceived products and suffer the same repetitional damage as Rabbit and Humane.

It’s not just the startups that are struggling with this affliction. Volkswagen had thousands of ID.3s stranded in fields because their software needed to be updated manually before they could be shipped

The most notable example is the Tesla Cybertruck. No matter what you think of its aesthetic or cultural significance, the amount of promise it embodied is impossible to deny. And yet its execution is so half-arsed that owners are being left stranded and disappointed by an encyclopedia of product failures.

These pile insult on top of the injury of Tesla’s failure to deliver the product on time, at the promised price, with the promised range, or with key pieces of promised technology.

Fisker too has fallen victim to a rushed market entry. It wasn’t just the Ocean’s software that was unfinished – prompting Brownlee to call it the worst car he’s ever reviewed. A lack of internal processes meant that customers’ payments for vehicles couldn’t be tracked and, in some cases, were lost all together. The Oceans, once retailing for up to US$63,000, are now unsaleable at less than half that thanks to the destruction of the company’s reputation.

It’s not just the startups that are struggling with this affliction. Volkswagen had thousands of ID.3s stranded in fields because their software needed to be updated manually before they could be shipped. Unfortunately, a software update couldn’t fix the much-criticised touch controls…

More recently, multiple software faults left journalists and owners stranded in their new Chevrolet Blazer EVs, right at the point at which GM was telling the market that they were going to go it alone on software development. The issue was so bad that GM issued a stop-sale of the much-hyped product, and while the car maker said that it effected a “limited number of cars”, to a car-buying public cautious about transitioning to software-heavy EVs, the column inches generated by the situation will have suggested otherwise.

Unless these things are genuinely useful to the consumer, they’re unlikely to have any meaningful long-term positive impact on the brand, let alone top-line growth

So how did we get here? How did an industry with such a hard-won reputation for quality and safety start letting things slip?

Firstly, many industry leaders, their boards, and their shareholders fell in love with Silicon Valley stock valuations and the “hardcore” culture – summed up in maxims like “move fast and break things” – that appears to have delivered them.

“Get the product to market, bugs be damned!” they might cry. “We’ll fix it OTA!”. Anyone who’s ever had to work this way knows that the solution is rarely as simple or as inexpensive as it first appears.

Secondly, we seem to have confused *smart* for *useful*. The ability to bend code to our will has opened up untold opportunities to create “smart” features and functions, to say nothing of opportunities to generate new streams of revenue through subscription (those stock valuations again).

But unless these things are genuinely useful to the consumer, they’re unlikely to have any meaningful long-term positive impact on the brand, let alone top-line growth. Paying $12.99 to [change the colour] of your ambient lighting? Yeah, no…

Maybe we’re better off underpromising and overdelivering

Thirdly, the industry is falling victim to a rash of overpromising and underdelivering. At its worst, this sees people dying behind the wheels of their Teslas, believing that Full Self Driving did what it said on the tin. Less tragically, we increasingly learn that marquee features won’t be available at launch, but will be enabled at a later date, a worrying suggestion that the car is not, in fact, ready for prime time.

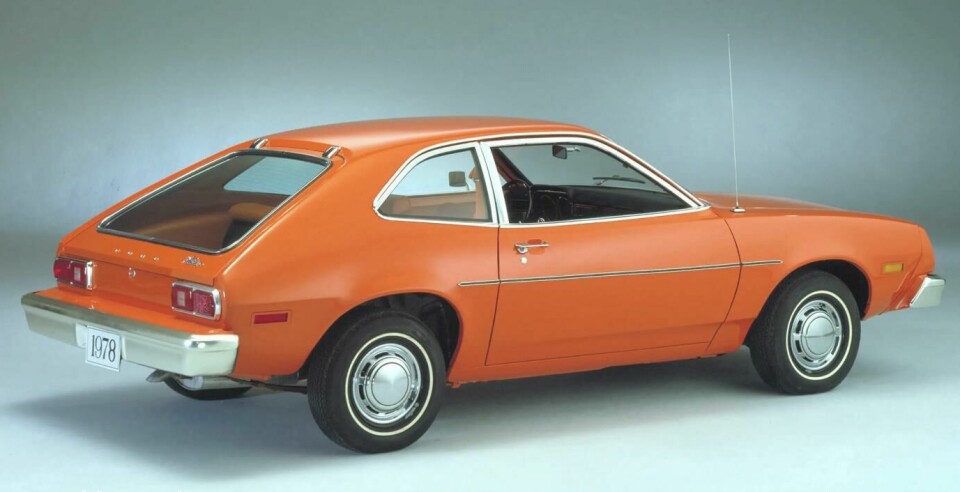

They say a reputation takes years to build and only seconds to destroy. And sure, it is possible to rebuild. Ford moved past the Pinto and the Firestone tyres. Mercedes-Benz moved past the rust era. Audi rolled on through unintended acceleration.

But recovery is slow, costly, and down to factors outside of your control, like how quickly your customers are willing to change their mind. In an era in which we’re asking customers to put their faith in an entirely new technology – one that’s not without its compromises and challenges – maybe we’re better off not needlessly risking our reputations. Maybe we’re better off underpromising and overdelivering.