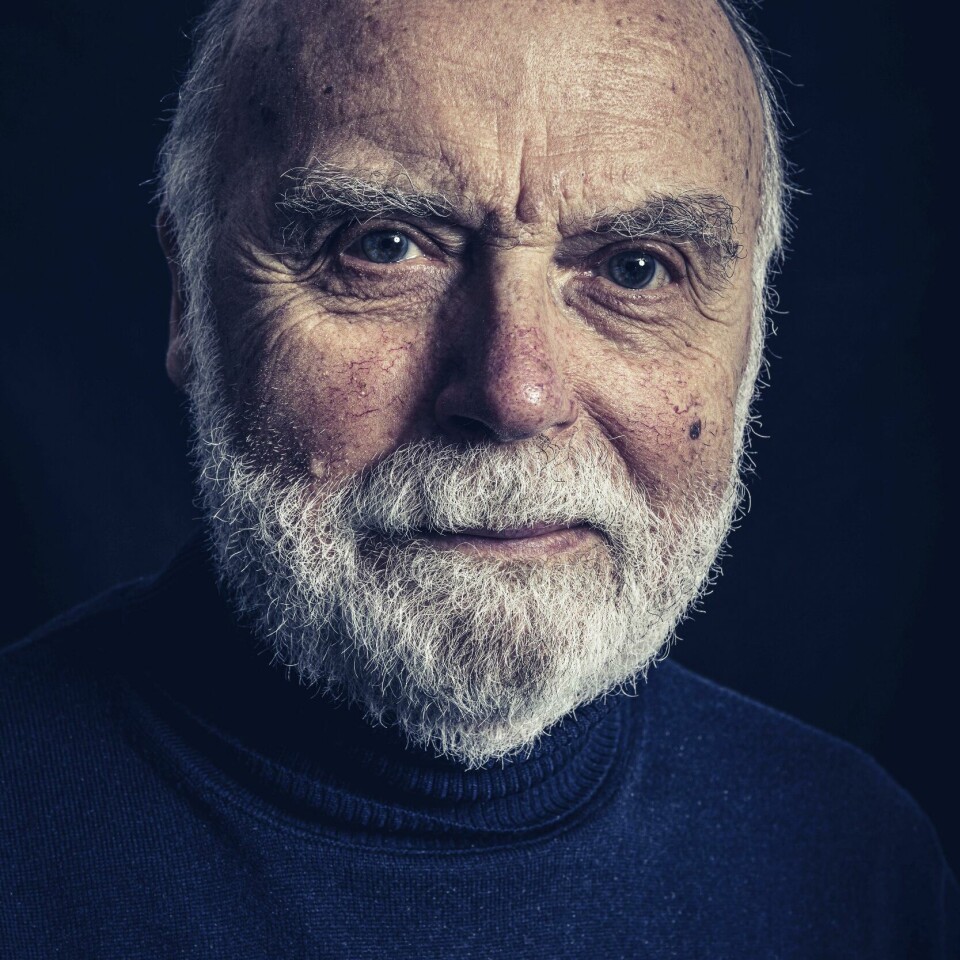

In memoriam: Bruno Sacco (1933-2024)

Bruno Sacco, Italian Mercedes-Benz design veteran and one of the most significant names in the industry, has died aged 90

Bruno Sacco’s professional career started when he joined the famous German brand in 1958, under the watchful eye of the de facto second-ever head of Mercedes design, Friedrich Geiger, who had been granted a small ‘styling department’ within the larger Body Design division in 1955.

Sacco was hired after his contemporary Paul Bracq as only the second stylist within the team. An early design hit came through his significant role in the creation of the 1963 Mercedes-Benz 600, which managed to stay elegantly proportioned in many guises – from long wheelbase to rear-seat, partial open-top ‘landaulet’ – and went on to find acclaim through celebrity owners, including music legend David Bowie and Hollywood actor Jack Nicolson.

While the 600 was a rather rational and formal early-60s design, Sacco was perhaps best known during this decade for his late-60s dramatically wedgy, gull-winged and delightfully flat-orange prototypes, the 1969 C111 and 1970 C111-II. Indeed, those designs still resonate strongly with today’s Mercedes’ design team, to the extent that the C111-II was recently reimagined in 2023 through the Vision One-Eleven concept.

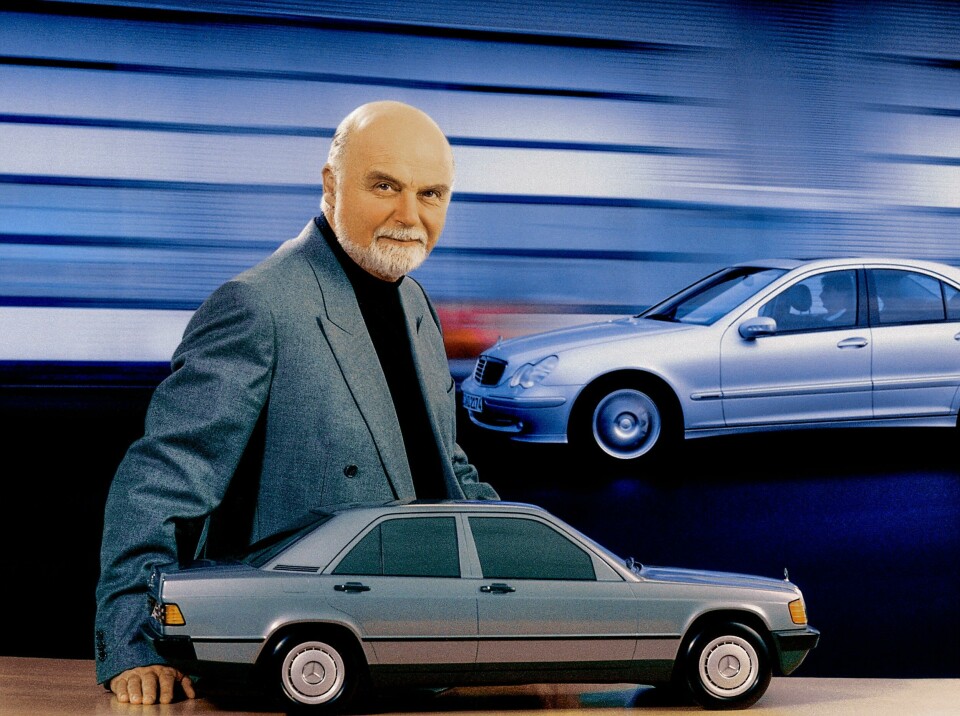

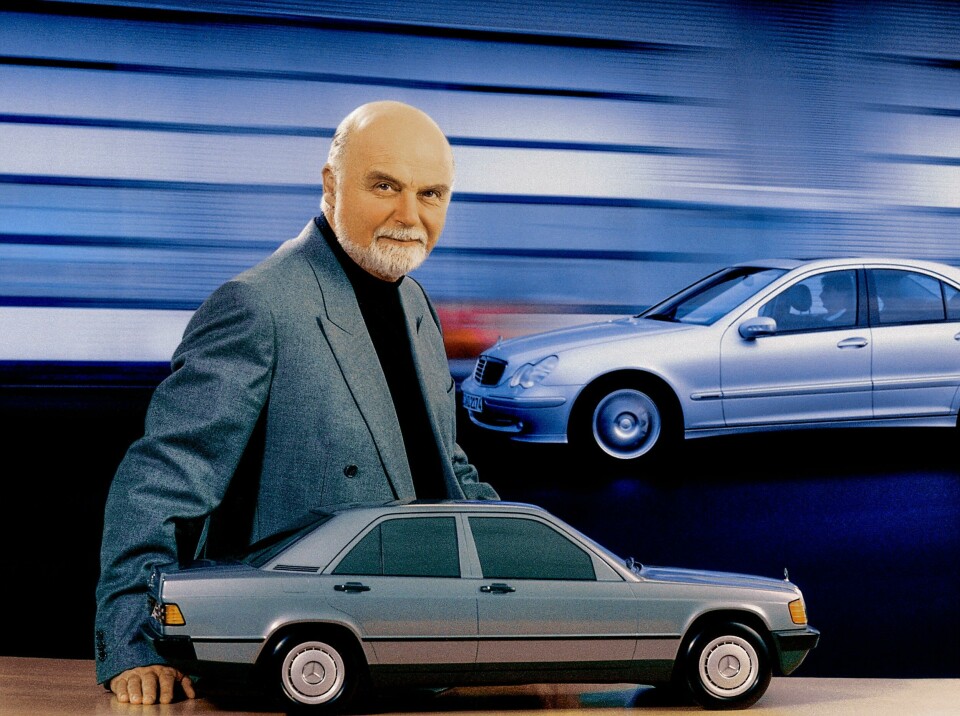

In 1975, Sacco took over from Geiger to effectively become the third head of design in Mercedes’ long history. There he took the brand towards a more wedgy, edgy and altogether more solid direction, with crucial designs like the W124 model series E-Class forerunner and W201 model series 190 ‘Baby Benz’ C-Class predecessor.

The latter 190 design was probably his finest moment, introducing Mercedes to a whole new customer base, and is still revered by car design aficionados as a classic example of the compact ‘three-box’ saloon genre. Indeed, as the current – and fifth – Mercedes design boss, Gorden Wagener, commented some years back: “The 190 is a typical Bruno car, monolithic, clean, everything in the right order”.

Things being in the “right order”, would seem to stem from Sacco’s upbringing. He was the son of the commander of a mountain infantry battalion and a geometry expert, graduating at just 17 in his hometown of Udine, as the youngest geometer in Italy. He then studied mechanical engineering at the Polytechnic University of Turin in 1952 and got some project work at independent Italian coachbuilders Ghia and Pininfarina. But he found permanent employment at Mercedes (then Daimler-Benz) in 1958, married a girl from Berlin (Anne-Marie) in 1959, had a daughter in 1960 and then settled in Germany.

From 1974-1999, Sacco oversaw every major car Mercedes produced and from 1993, every van (after he became a company director). A distinctive detail that contributed to the chunky look of Mercedes cars during this period is the protective lower side strip he introduced in 1979 and which featured on the 190 C-class predecessor (W201 Series 1982-1993), E-Class forerunner (124 Series 1984-1997), S-Class (140 Series 1991-1998) and SL sportscars (129 Series 1989-2001).

Sacco espoused a design philosophy of “horizontal homogeneity”, so that products from the same company, whatever size or shape, should share visual design links, as he famously declared: “A Mercedes-Benz needs to look like a Mercedes-Benz”.

He was also a firm believer in “vertical affinity”, meaning that successor models should not render their predecessors visually obsolete. As he has been quoted regarding one of his most famous and also favourite designs, the 1989 SL Roadster: “Another thing that’s just as important is harmonious model progression – the next model should never make the previous model look old.”

Sacco was still at the design helm during the 1990s when the Mercedes range expanded dramatically, into both larger segments – in the shape of the 1997 M-Class SUV – and smaller ones, with the innovatively packaged 1998 A-Class mini-MPV. Strategically, Mercedes’ design department structure also changed and expanded under Sacco’s watch, notably with the addition of advanced and regional market specialist design studios opening in Carlsbad, California, USA in 1990 and Tokyo, Japan (1993) plus an interior design studio in Lake Como, Italy (1998).

The latter studio, in particular, seemed close to Sacco’s heart and not just due to its beautiful northern Italian location. The 18th century mansion where the designers worked was a bit special. Previously occupied by the Versace fashion brand – some of that designer’s signature medusa heads could be found around the building – and with polished wood floors and ceilings painted with classical style murals, the feel inside was more like a boutique hotel than a satellite office of a corporate giant.

Despite being a little small to create full-size interior bucks – although many did get made there – its locale was nonetheless perfect for easy access to Turin’s coachbuilders and Milan’s furniture and fashion trends. Its dolce vita lifestyle also attracted many designers to the brand who might not have been so keen to work and live in Mercedes’ less glamorous hometown of Sindelfingen.

Despite believing in design longevity – a key attribute to Mercedes cars created under his watch, many of whose lifecycles were 10 or more years, rather than the now more common six – Sacco was not a subscriber to the design philosophy that “form follows function”. As he has been quoted by the Automotive Hall of Fame, in Dearborn, Michigan, where he was inducted in 2006: “There is no primacy of technology over design, or design over technology. The aesthetics of a product can never hope to make up for poor-quality technology.”

But ultimately, the vast majority Sacco’s designs were successful in visually reinforcing the idea of Mercedes vehicles being ‘built to last’, and this should ensure that his design legacy is similarly robust.

RIP Bruno Sacco (12.11.33-19.9.24)