The days of textures sold on a roll are drawing to a close as new material technologies arise

New technology has unlocked fresh possibilities in many areas of car design, but in the particular field of interior textures, the availability of versatile 3D printing has proven especially fruitful. It now permits new surface grains to be designed and developed without large upfront costs. For car designers, this opens up texture as a versatile medium for expressing brand identity or accentuating

form design.

“In the past you could walk around a show and see the same grains on cars from many different OEMs,” notes Mike Miller, head of design at Architexture’s European studio in Manchester, UK. As Miller explains, this outcome arose because unique grains were very expensive to develop. “You used to wrap prototype components in off-the-shelf PVC foil,” he recalls. “It would cost tens of thousands to create your own roller for a new pattern, and if the grain didn’t work out then whoops, you’ve made a big hole in your budget.”

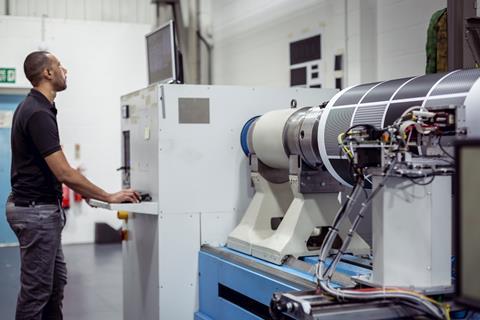

Today, Architexture can create tailored textures without such prohibitive investments. “We’ve developed a process called Rapid Texture Prototyping (RTP),” Miller says. “It allows you to explore new design concepts and see them very, very early in the design cycle, as 3D textures – not as images or VR pictures, but as real-world physical samples.”

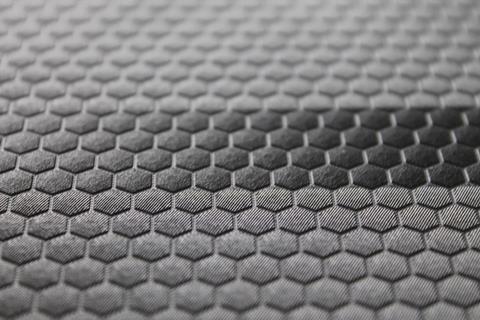

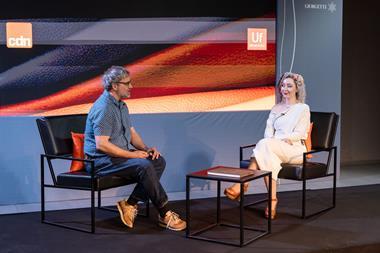

Using the RTP process, new textures can be 3D-printed in large sheets, up to 1.2 metres wide and two metres long, at up to 3500dpi definition. Silicon moulds taken from this shape are used to create textured skins for wrapping around form models or prototype parts, which are then painted by Architexture’s model makers to achieve specified colour and gloss levels. “Design studios can accurately simulate textured production parts,” explains Lilana Nicoghosian, (pictured right in the US studio) chief designer at Architexture’s North America studio in Detroit, Michigan. “These skins are used for show vehicles, market research properties and photo-shoots.”

The company offers a full design, verify and produce (DVP) process. As a subsidiary of Standex Engraving Mold-Tech, it can draw on knowledge of every step from initial sketch to production tooling.

“Design can incorporate many attributes, such as functionally-driven textures, brand DNA, and input from trends research, to name a few,” Nicoghosian says. “As we work with our clients through a project’s evolution, we gain knowledge of the material, haptic and sensory needs, as well as cost, timing, and production processes for each part. We work hand-in-hand with the customer’s design studio to ensure designs are feasible for production, and take advantage of rapid prototyping throughout the design process, from 3D printed textures in the early stages to fully wrapped production-intent parts as the project matures.”

For Architexture’s clients, creating bespoke textures can reap rewards beyond the aesthetic, as demonstrated by the Cut Diamond grain developed for Jaguar Land Rover’s Velar SUV. “JLR owned the intellectual property, so they could put it out to tender,” Miller notes. “Instead of a supplier saying, ‘Here’s our range of grains and this is what they cost,’ JLR was empowered to negotiate the best price across the whole community of material suppliers.”

With connected studios in the US, UK and China, the Architexture team can bring both local and global knowledge to bear throughout a

bespoke design project. Miller explains that a Chinese OEM with a European studio might begin by working with the Architexture team in the UK, but complete the journey to production alongside Architexture designers in China. “That’s a process we’ve followed with more than one OEM,” Miller says.

“China’s market is an emerging, fast-growing one,” adds Cole Chen, design manager at Architexture’s Asia Pacific studio in Suzhou, west of Shanghai. “Chinese designers have to be flexible, which provides us with many opportunities to innovate and improve.”

Chen cites recent work for a Chinese OEM that wanted to strike a balance between traditional leather grains and more technical surfaces, a tricky brief that would be difficult to meet without the ability to quickly explore multiple options. Cole adds that the service offered stretches beyond textures alone to include all aspects of colour, materials and finish.

“Architexture offers a unique opportunity to develop surface finishes and textures that underscore brand identity,” adds Lilana Nicoghosian. “We take a holistic approach to understand the message behind each product, and work with our clients to create the perfect texture.”

Work carried out for Tata over the past 18 months provides a good example, Miller says. Architexture has helped the Indian OEM apply its signature tri-arrow motif – or jaali – to the interior of its Geneva 2019 show car.

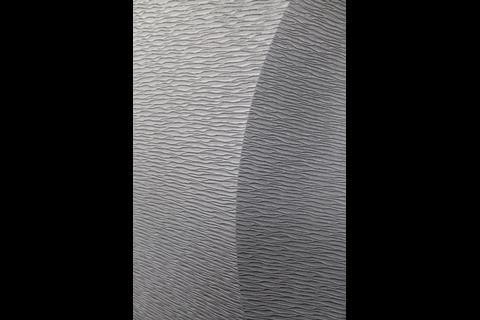

The jaali pattern has been applied in “deep, aggressive, but absolutely beautiful” new ways, says Miller. “It’s on the IP and the doors at different scales, and it changes form across the IP, from deep and heavy to very light as it nears the windshield. It morphs and changes its graphic nature across the whole landscape of the interior.”

The result is unique, brand-reinforcing surfacing with both visual and tactile qualities that would be impossible to achieve with textures unfurled from a roll.

This kind of surface innovation is poised for wide uptake, predicts Cole, because it enables more emotive design. “The car of the future is not only a means of transportation,” he notes. “Today’s ‘efficient’ and ‘modern’ design approaches will lose their advantages. Design with a technical feeling is coming to an end and aesthetics based on emotion, feelings and expressiveness will become more attractive.”

Miller adds: “Architexture is not just about designing textures, it’s about designing new ways of doing things.” He goes on to outline a new process that Architexture and Standex Engraving Mold-Tech are developing to create production tooling straight from prototype parts wrapped in Model-Tech skin.

“We know it works, we just need to be able to trim models to the required standard,” Miller says. “If we can do this, it would let OEMs produce tooling with a variety of different textures much faster and cheaper than ever before. You’d be able to grain a model, make a tool from it, then re-grain the model with something entirely different and make another tool. Then you can very easily make the same component with different textures, meeting different aesthetic requirements across your customer base.”

This kind of process could help free the creative ideas expressed in concept cars from the heavy hand of large-scale production, giving more opportunity for customisation. “By bringing design and technology closer together, it could open up a completely new narrative about what is design, what is acceptable, and what is possible,” Miller predicts.