Car Design News spoke to Magna Exteriors experts Larry Erickson, Global Director of the Exteriors Design Group, and Brian Krull, Global Director of Innovation – Exteriors, about the design possibilities that spring from the humble rear hatch.

Car Design News: the current popularity of SUV body styles must be driving a boom in liftgate manufacturing. What has been your experience at Magna Exteriors?

Brian Krull: The global market for liftgates is exploding. Over the next six years we’re expecting to see around 20% compound annual growth in plastic liftgates. That’s a $4bn opportunity. With the recent launches of the 2019 Jeep Cherokee and 2019 Acura RDX we’re the largest plastic liftgate supplier in North America, and we’ll be the largest in the world with several upcoming launches in Europe and China.

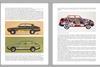

Magna recently launched high-volume thermoplastic liftgates on the 2019 Jeep Cherokee…

…and the 2019 Acura RDX

We view the liftgate as a module, so we not only mold all the components and assemble them but we also bring the fixing elements together. We have cross-group collaborations within Magna for things like power systems and latching. So we offer a full-service approach for OEMs.

CDN: It’s obviously helpful to have one supplier manage a complex assembly, but what can a Magna tailgate offer from a design standpoint?

Larry Erickson: The ends of the vehicle are always the most complex as far as form goes. With stamped metal you face those age-old limitations of draw depth, which means you have to make the part out of multiple pieces. With a composite liftgate you can easily pull the form around the vehicle’s side, which has become a trend among newer SUVs.

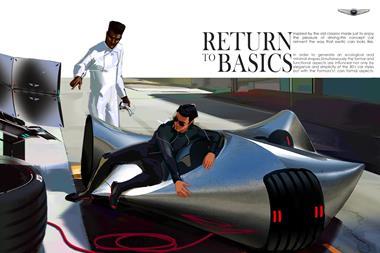

Composite materials enable greater vehicle drama in the design of liftgates

As shapes have become more complex, dealing with aerodynamics and the need to taper the body form, the shut faces have moved around to the side of the vehicle, from the back. That allows you to achieve several things, including making the opening as large as possible.

When you make a liftgate with a composite, you can put a lot more form into it. It’s not just depth of draw but retention of shape, the type of shape, the sharpness of the features and in many cases there’s also the weight aspect. To do a wraparound shape with conventional materials would usually drive the overall weight higher.

Krull: Weight is really important given the trend toward plug-in and electric vehicles coupled with the popularity of SUVs. There’s an extremely strong focus on saving weight at the rear of the vehicle. Weight also comes from all the features we’re adding into vehicles. With the sensors and equipment needed for autonomy and new mobility concepts there will be an even stronger push to offset the weight that’s being added. That’s one of the things that we’re addressing through our composite and thermoplastic offerings.

CDN: Do you foresee plastic and composite panels becoming more common in other parts of vehicles?

Krull: Passenger doors offer a great opportunity for mass reduction. Roof panels and assemblies are another area where plastic or composite solutions are likely, and then within vehicle structure there’s a lot of opportunity to cut weight with advanced thermoset composites like carbon fiber reinforced SMCs [sheet-molded composites].

With advanced thermoplastics we’re also looking not only at ways to reduce weight compared to the typical materials of today, but to do it while increasing stiffness and strength with materials like carbon fiber, or even reclaimed carbon fiber to keep costs down.

We’re also looking at future materials like graphene and what they can contribute from a materials perspective [our prior article on materials innovation outlines the potential for graphene in carbon composites].

CDN: What other design possibilities might we see enabled by plastic panels that would be tricky to achieve by other means?

Erickson: Texture and surface quality can be controlled a lot more easily with an injection molded part. It allows better retention of detailed forms than stamped steel, and it gives you much more design freedom. Vehicles right now are pretty smooth surfaced but that may not always be the case.

A composite panel allows surface options such as grained patterns and complex textures.

There’s also the issue of integrating sensors and cameras for perceiving the environment, which is often easier to accommodate in a plastic part [see our earlier article on sensor integration for more details]. The lighting going into liftgates is constantly changing. Molding tends to be a little friendlier in getting the level of detail and the level of interaction you need.

Then imagine a world where a vehicle might operate in both directions – if it’s electric and autonomous there’s no reason why it shouldn’t – and that could open up more applications for liftgates than you first think. Loading passengers in the front and rear would be new. There’s a lot of uncharted territory out there, and I think the boundaries for autonomous vehicles remain unpredictable.

CDN: Magna pioneered mass production of carbon fiber hoods for the 2016 Cadillac ATS-V and CTS-V. What have you learned from that experience?

Krull: That was a significant innovation in the use of carbon fiber. In the past the main issue has been cycle time, and we kept that in check using prepreg materials and compression molding process to speed things up and decrease cost. There is still a cost premium that limits it to high end vehicles but our continued goal is to develop not only the materials but the processes to make carbon fiber more affordable, because it offers one of the best strength to mass ratios of any material on the market.

Erickson: Different customers have different volume expectations. Around here, high volume is 300,000 a year and up, and we’re probably a good distance from those kind of volumes. But in lower numbers, on performance and luxury vehicles where mass has a high value, you’ll see more use of carbon fiber.

Krull: A lot of the investigation we’re doing right now is in structural applications, looking at chopped, random carbon fiber SMC materials. For the exterior of the vehicle, one of the things we’d really like to achieve is the introduction of carbon fibers into thermoplastics, which would offer very fast cycle times and the potential for very high volumes.

CDN: What advice would you give to designers thinking about these topics, whether for liftgates or other applications?

Erickson: Be proactive and look at these issues early enough to understand how the constraints and design objectives can work together. Sometimes that takes longer than conventional program timing allows, which is a challenge. For advanced design teams looking at long-term issues, at the next platform or the next series of vehicles, we’d like to support an ongoing dialog and work with them from an early stage.