“What is a portfolio?”

That was young Pete Brock’s rather inauspicious beginning to his design education. A teenage phenomenon on the customizer circuit, he had won the Oakland Roadster Show Grand Prize twice, but now walked amazed through the halls of Art Center College of Design, seeing on the walls drawing of cars he had only glimpsed in his imagination. But here, the designers of the future were actually creating those cars – going on to Ford, GM, and other manufacturers to see them become reality.

The Fordillac – a custom Ford with a Cadillac engine – was a prize winner for Pete Brock. Its sale paid for his tuition at Art Center

Brock, a bit starstruck, walked into the office and asked to be enrolled immediately. When the registrar asked the portfolio question, and then patiently explained what a portfolio actually was, Brock was undeterred. He walked back to his car, spent a few hours drawing cars on the blue-lined pages of a three-ring binder, and walked back into the building to submit his portfolio. He was accepted on a provisional basis, pending the final approval of his instructors.

Pete Brock, design prodigy and designer of a number of famous sports cars

A design prodigy, his work was advanced, but lacking in the fundamentals of design basics and presentation. Brock credited his instructors and fellow students with shaping his talents into marketable skills. But Brock eventually ran out of tuition funds, and was encouraged to contact Chuck Jordan at GM. Jordan was charged with finding fresh talent and he gave the young Brock a chance, bringing the young man into GM studios at age 19, the youngest designer ever hired at GM.

The Alfa Romeo Disco Volante (1953) had an enormous influence on the nascent Stingray programme

Pete worked on interesting projects at GM, but none more fascinating than the Corvette Stingray project, spearheaded by Bill Mitchell. The project was twofold: to develop a future for the production Corvette, and to develop a racing version for the track – despite the industry ban on factory-sponsored a racing (a ban put in place to deflect severe restrictive legislation then being considered in Congress).

Mitchell established a competition for design ideas, and Brock’s sketch of November 22, 1957 was judged the winner. Development started on the project, and Brock helped in the studio that worked on a racing version.

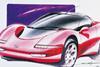

Brock’s Concept Sketch of 1957 was the basis for the Corvette Stingray of 1963

But Pete Brock was, at his heart, a Hot Rodder. He missed the track, the workshops, the fixing of cars. While at GM, he worked in the evenings on a Cooper race car that had run at LeMans. He didn’t want to just draw cars, he wanted to build and race cars.

Brock would leave GM in 1959 and return to Southern California. The Stingray production car would be developed by others. Other projects developed by Brock faded away.

Back home at last, Brock would eventually become Carroll Shelby’s first employee. His dream for his work at Shelby was to design and build on weekdays and race at weekends. But Shelby already had enough racers and mechanics so Brock was designing cars, to be sure, but also livery, letterhead, signage, jackets and all the ancillary graphics of Shelby’s business. Interesting, but not exactly what he had dreamed of. Still, Brock got to design the Shelby Daytona, the Lang Cooper, the Nethercutt Mirage, and the P70, all recognized as sports car classics of the era.

Carroll Shelby failed at chicken farming, but succeeded at racing. Enzo Ferrari offered him a job. Shelby turned him down

Carroll Shelby, the failed chicken farmer who would become an automotive legend, is remembered for his brilliant racing and the engineering that created masterworks of auto racing history. But a heart defect sidelined him from the racetrack, and he soon discovered that his real talent was salesmanship, and assembling teams of gifted drivers, mechanics and craftsmen of all types – including a few talented designers.

The Shelby Cobra. The AC Cobra never had it so good. Raced like it, too

Once, when Lee Iacocca was visiting Shelby American’s shop in Venice, California, he remarked how impressed he was with the busy facilities and the dedicated team. It seemed the perfect shop for the plans he had for a Ford performance program.

“Shucks,” Shelby said, “I’m not an engineer. I’m not even very smart. The only thing I understand is human nature. I just like to bring the right people together and see what happens. I think I’ve put the right people together at Shelby American.”

Iacocca recognized a fellow hustler when he saw one, and eventually hired Shelby to assist Ford in the Blue Oval’s nascent racing program. The two would remain colleagues and friends for decades.

Shelby (right) and Lee Iacocca – two of a kind, and good friends for decades

Carroll Shelby was not an easy man to work with even on a good day. Restless and impatient, he talked loudly and quickly in his almost indecipherable Texas drawl, a habit he had developed from years on the racetrack. He moved from station to station around the shop, checking on projects and berating those he found lacking in their duties.

One exasperated secretary quit, claiming, “You have to run 90mph to keep up with him, and I’m just an old-fashioned 80mph girl!”

Only the most talented and dedicated lasted. Dreamers and slackers were run out of the shop by the intensity of the place and its mercurial boss. Still, there were always plenty of hands to work on Shelby projects, and they were insanely dedicated. Shelby would characterize his crew as “hot-rodders trying to prove that they weren’t the dipshits everyone in the world thought they were.”

The Cooper-Monaco-based King Cobra. A mid-engined terror on the track

It showed in Shelby’s success at the racing circuit. His AC Cobras and Cooper Monaco-based King Cobras were terrors to other cars on the track and brought home a case full of trophies.

The Lang Cooper 2. Its design was rumored to have influenced the design of the P70 – actually, just the opposite was true

But looking ahead, Shelby sensed there would be trouble for the forthcoming series that would lead to the famous Can Am races that were to start in 1966.

He had Pete Brock sketch out a new race car, loosely based on the King Cobra, but with significant improvements. The body was to be much more aerodynamic. The engine was to be an alternative to the standard 427 Ford V8 which had proven itself in stock and sports car racing, but Shelby thought too heavy. He had an idea for a new lightweight, stroked and bored, Ford 289 V8 with a high-flow head.

Alejandro de Tomaso – Argentine transplant and political refugee turned racer, then automaker

But time was short and Shelby needed to move fast. He contacted Alejandro de Tomaso in Modena, Italy. Also a former racing driver, de Tomaso was interested in the concept of the car, and had a chassis and transaxle concept of his own. It seemed like the perfect marriage – two high-performance racing car assemblies which could be married together and covered with a body designed by Brock, a world-class car designer.

The P70 as finished. An instant classic

De Tomaso agreed to take on the project on an accelerated (read: impossible) timetable, modify the Ford V8, mate it to his chassis and create the body from Brock’s drawings. A total of five cars were to be built.

Greatly improved aerodynamics characterized the P70

Engines and drawings were sent from Shelby American to de Tomaso in Italy. Work began, but soon it was apparent that the Argentine would not meet Shelby’s compressed timetable. Additionally, Shelby was not happy with de Tomaso’s interpretation of Brock’s design.

The engine that scuttled the Shelby/de Tomaso relationship lies under that cover

Brock was despatched to Italy to sort things out, but de Tomaso was not pleased to see the young American walk through his door. Brock would later recall, “…Shelby sent me over to personally see that everything was built correctly — de Tomaso was ‘insulted’ that Shelby had sent someone to make sure he didn’t mess up again.”

The P70 interior – a study in minimalism, even for a racing car

Brock tried to make the best of a bad situation. He withdrew from de Tomaso’s shop and let the Argentine and his team wrestle with the complexities of the engine modifications. He spent most of his time over at nearby Carrozzeria Fantuzzi, where the body of the P70 was being constructed.

The rear of the P70 showing the adjustable wing – a racing first

The Carrozzeria Fantuzzi was not a large shop, but had strong ties with Maserati and, at times, Ferrari. There Brock found some kindred spirits and a more receptive audience for his design ideas. He, in turn, found a great appreciation for the Carrozzeria’s craftsmanship and fabrication techniques. In this collegial atmosphere the construction of the body moved along at a good pace.

As Brock would recall later, “their methods of construction were totally different than those we use here in the USA and also in the UK. They worked in wire form, not wooden bucks, with templates at each ‘station.’ Fast, simple and far more illustrative of what will be built. Easy to change mid-build if it becomes evident that change is needed. Very practical.”

And then one day, it was all over. Carroll Shelby had grown increasingly impatient with the slow pace of the engine development as it dragged on. Additionally, Shelby had landed a contract with Ford to help build the GT40, as the Blue Oval ramped up its program to unseat Ferrari at Le Mans. The money and opportunity was just too good to pass up.

Peter Brock was abruptly called back to the States, and the Shelby P70 project was officially dead. But...

NEXT WEEK: Alessandro De Tomaso must snatch victory from the jaws of humiliating defeat. Join us to learn the fate of the P70 and the remarkable car it would influence.

Photos: © Hemmings/Amelia island Concours, Top Speed